Tag: islivig

Clearances 1851

Calling Breanish

Mealista v. Ardroil

By long and solid tradition in Uig, the spot where the Uig Chessmen were found in 1831 is held to be the Bealach Ban, a hollow in the dunes in Ardroil. In November of last year, a paper by Dr David Caldwell et al in Mediæval Archaeology proposed that, on the evidence of the Ordnance Survey Place Names book compiled by contractors from local information in the 1850s, the findspot may have been a few miles away at Mealista. Anna Mackinnon, Ardroil, wrote an initial response countering that suggestion and gives more evidence from the Place Names book here. This piece appeared earlier this month in the Uig News; thanks to Anna and the Uig News for the opportunity to republish it. Meanwhile Dr Caldwell will be speaking in Uig about the Chessmen on Thursday 4 March. Further detail will follow.

Over the last few weeks, I’ve been delving into the book of place names collected by the very first Ordnance Survey of the 1850s to find out for myself what’s actually there and to work out how much import can be given to the entry that states that the Chessmen were found in Mealista, in the ruins of Taigh nan Cailleachan Dubha. The Place Names book is easily accessible, on microfiche in the Stornoway Library.

I have to say that it’s an example of meticulous paperwork, a colossal amount of painstaking effort must have gone into its compilation but to the 21st century eye, it looks fussy and overdone. It’s handwritten and ruled out in column after column: place name; its correct spelling; any other known variation of the spelling; the location; the English “significance” i.e. translation of the name; the names of the person or persons who were the authorities for the information and of the Ordnance Survey Clerks who wrote it all down and, finally, a column for comments.

We used to be advised as students not to use it as a reliable source as the information was only as good as the knowledge of the informant and also, because its accuracy could have been compromised in translation. There’s a long time since I last looked at it and this time round, I found its main impact, apart from its painstaking “clerkery,” was the sheer volume of place names in the parish of Uig. Going through the pages nearer home, I felt as if I was meeting old friends as place names jumped out at me from the screen, names I used to hear in daily conversation, which are now rarely, if ever, aired.

I was also intrigued by the names of the local informants of the 1850s. I would really like to go back to it and list them all down to see how many can be identified with the help of the census returns. I found my great, great grandfather, Murdo Macleod, Gisla, (Murchadh Ghioslaigh) and his neighbour and brother-in-law, John Macdonald, (Iain Laghach) reeling off names. That pinpoints the collecting of place names to before 1853 and the Gisla clearance, after which all the Laghach family but two ended up in Quebec.

From memory, I was sure that the Chessmen were noted in the pages relating to the Ardroil area although the name Ardroil wasn’t in use in its present form as early as the 1850s. The farm was known initially by variations of Eadar Dha Fhadhail, such as Ederol. The entry about Chessmen is there, under the place name “Bealach Ban.” It reads, “A glen on the south side of Camus Uig, it is composed of sand. A few years back a number of carved Ivory images of horses, sheep and other animals were found in this glen. Signifies white glen or pass.”

On the trail of the Uilleam Dubh

Miss Ina Macdonald is appointed to Hamnaway

Civilised Children in 1874

The Centenerian

The Uig POs and their Postmarks

Crofting at the Upper End, 1958-9

Breanish and Islivig in 1959

Interned at Groningen in 1914

This unidentified sailor with the Naval Division is believed to be one of those interned in Holland in 1914. The picture was taken at Groningen, and comes to us from 10 Mangersta. Is he one of the Uigeachs listed below who spent the war in “HMS Timbertown”? The following was written by Dave Roberts for Uig News; more information about the 106 known internees from Lewis, and the conditions they experienced, are found at Guido Blokland’s comprehensive website.

This unidentified sailor with the Naval Division is believed to be one of those interned in Holland in 1914. The picture was taken at Groningen, and comes to us from 10 Mangersta. Is he one of the Uigeachs listed below who spent the war in “HMS Timbertown”? The following was written by Dave Roberts for Uig News; more information about the 106 known internees from Lewis, and the conditions they experienced, are found at Guido Blokland’s comprehensive website.

On 5 August 1914 the postman delivered buff-coloured envelopes to all the reservists. War had been declared. There was no reluctance to answer the mobilisation call, and those on the Island made their way immediately to Stornoway, thence to Kyle of Lochalsh, and eventually to one of the Channel ports. The most pressing military need at the time was for infantrymen, not for ships’ crews, so the Naval Reservists found themselves issued with a rifle and ten rounds of ammunition. Their training had been as crew for warships, and the handling of big naval guns, not as infantrymen! But on 5 October they were transported to Antwerp in Belgium, via Dunkirk, to attempt to defend the strategic port from the advance of the Kaiser’s Army. The defences were built in the nineteenth century and were no match for the heavy artillery or the devastating fire from the ‘Big Bertha’ mortars. The ill-equipped and inadequately trained Naval Brigades had no chance and held out for less than three days.

They were facing overwhelming odds, and despite orders that they were to defend this strategic deepwater port at all costs, it was obvious that a retreat was necessary. There were also specific orders that on no account should the Naval Division be caught in Antwerp. Eventually the orders came to fall back, and two of the Brigades did so, but for some hours the third remained ignorant of the withdrawal. 3,500 men reached the Burght, crossed the River Scheldt by pontoon bridge and marched to St Niklaas, where they boarded trains and escaped. The other 1,500 men of the First Brigade, consisting of Hawke, Benbow and Collingwood Battalions, finally got their evacuation orders but when they arrived at the river the bridge was no longer in place. Fortunately there were some small boats available for ferrying them across, but valuable time had been lost. They arrived exhausted at St Niklass early on the morning of 9 October.

All the transport had departed and they were forced to continue on foot to St Gillis-Waas. There they discovered that the railway had been blown up, and they were almost completely surrounded by enemy troops. In fact some of the Naval Brigade had already been captured, including John Maclean Ungeshader (Shonnie Gorabhaig), John Buchanan Brenish, John and Angus Maciver Crowlista, and Donald Mackay Valtos. Only three of the Uigeachs who were sent to Antwerp managed to escape that day: they were Kenneth Maciver Geshader, Donald Macritchie Aird and Angus Mackay Valtos. The rest were now facing capture, being wounded or even being killed by the fierce bombardment they were suffering. Commodore Henderson was in charge and the lives of his men depended on him making the right decision. Reluctantly he chose the safest option: rather than become prisoners of war, they would cross the border. Once they were on Dutch soil, and had surrendered their weapons to the Dutch Army, they became internees in the neutral country of Holland.

The Uig contingent were: Malcolm and Murdo Buchanan (cousins) Brenish; Angus Morrison Islivig; Angus Macdonald Geshader; Donald Morrison, John William Macleod, Angus Macaulay, and James Morrison Valtos; Donald Maclennan Cliff; Kenneth Nicolson Crowlista and Norman Macritchie Aird. Out of the twenty Uigeachs who were sent to Antwerp only Kenneth Maciver Geshader, Donald Macritchie Aird, and Angus Mackay Valtos avoided capture or internment.

The One Night Shieling

From an article in Uig News by Dave Roberts.

It appears that shielings were constructed so that one airigh could easily be seen from another, but it is said that very often the girls from a number of shielings would sleep in one building for company. The ancient shieling grounds for Brenish, Islivig and Mangersta were way beyond Raonasgail valley, in the moors north of Loch Craobhaig, at Fidigidh. The people of Carnish had their shielings by Loch Raonasgail, and at Ceann Chuisil. There are also ruins of old shieling structures closer to home, west of Mealisval, Cracaval and Laival. In the late nineteenth, and into the twentieth century, shieling activity was largely restricted to these closer locations.

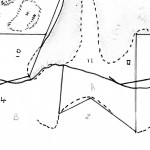

About half a mile from Tealasdale is one of the shieling grounds of Old Mangersta, situated north of Ron Beag and west of Loch Faorbh. At the west end of Tealasdale is Sgorr Reamher and Bealach nan Imrich – “the pass of the flitting”, and below the Sgorr is the ruin of a very large and well built airigh. It is marked clearly on the first edition ordnance survey map. Its location is not very inviting. It is sheltered from the easterly winds but not from the southwesterlies. Even in summer the sun does not reach it until well into the day. This is Airigh na h’Aon Oidhche – “the one night shieling”.

Supplies for Islivig School

The Hattersley Loom

Dol’ol at the loom (photo by John Blair). From an article for Uig News by Dave Roberts:

After the First World War there were ex-servicemen who had lost a hand, and one of the reasons for introducing the Hattersley domestic semi-automatic treadle powered loom to the island, was to give them an opportunity to make a living for themselves. Originally designed for the Balkans, Turkey and Greece, these looms eventually caught on for everyone in Lewis and Harris, because of the superior speed of cloth production and the more intricate patterns they could weave. Lord Leverhulme’s interest in the industry, coupled with the serious decline of the herring fishery and the poor price of cured fish from the long line fishery, meant that weaving became a much more important part of the island economy. He had great plans to build weaving sheds close to townships to house a number of Hattersley looms. The weavers would be employed from nine to five, six days a week, weaving tweed for a wage. However this arrangement did not suit crofter-weavers, who would only weave when the croft work allowed, and the idea was eventually dropped.

Hugh Mackay, Carishader, bought the very first Hattersley loom in Uig; it was a single shuttle model. He was a marine engineer, trained in Glasgow, and could strip down the loom and reassemble it without difficulty. If he had a problem, he had no one locally to ask for advice, so he would get on his motorbike and go to Stornoway. However he admitted that quite often he had forgotten the solution, by the time he got back home! In 1936, John Buchanan of No7, Valtos, organised a meeting at Valtos school for local people. Pat Skinner from Kenneth Mackenzie Ltd was there and they arranged for Alasdair Hare from Lochs (mac piuthair Tharmoid Doinn), known as ‘am Breabadair’, to stay in the village for a few weeks. He went from shed to shed teaching as he went.