The Gathering

This account of the gathering of the sheep into the Gisla fank for the clipping was written by David Henderson and first published in the Scots Magazine in August 1995. These large-scale community gatherings are now, sadly, a thing of the past. There are more pictures in the gallery, and of the fank at Loch Suainebhat here.

In the diffuse crofting culture of the Western Isles, the summer gathering of the sheep from the moors is one of the main highlights of community life. The practice has remained virtually unchanged since the arrival of the sheep in Lewis, and is a ritual I, as an incomer on holiday from Musselburgh, was priviledged to take part in. The gathering made the highlight of my stay.

My uncle Jim and I woke at dawn. The weather looked poor – drizzle and mist hid the view of Loch Roag from the kitchen window. I was sure the gathering would be put off – wet weather meant damp fleeces, difficult clipping and hours of drying for the Blackface wool we were to harvest.

Donald Calum Morrison, our crofting friend from Valtos, arrived at 7am as planned, refusing tea and looking skyward. “It looks awfully dull,” he said, “but no one’s phoned me so the gathering’s still on.”

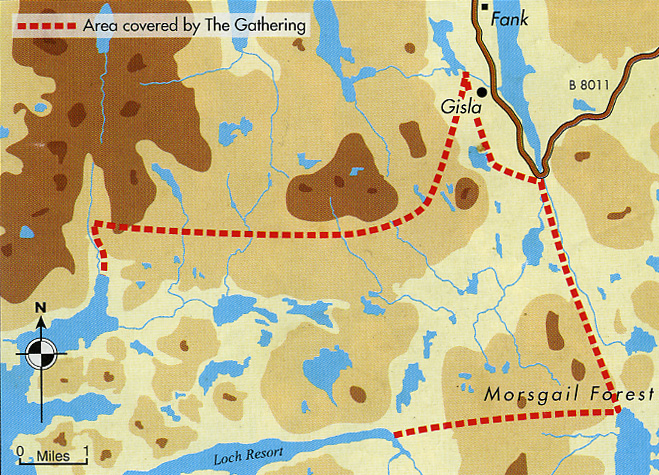

Soon I was huddled in the back of Donald Calum’s austere van, sharing floorspace with an excited sheepdog who seemed to know what was in store. We rattled and bounced down the single track road, through Miavaig and on to the road south, pulling into passing places from time to time for a competing car, Donald Calum waving to them with the easy grace of one used to the island etiquette. Then we reached Gisla for the start of the walk into Morsgail Forest, a barren moor between Lewis and Harris where the Valtos crofters’ sheep roam their common grazings.

More than a dozen cars were gathered there. A brief discussion took place in the rain. All the crofters were annoyed that the weather had closed in – during the fortnight before, it had been “just like the Sahara,” as one local put it. There were pensive faces, shaking heads, pursed ips and whistling through teeth. “If it doesn’t dry up soon, the wool will be soaked,” said one man.

“But if we don’t go now, we’ll have to wait for a week before the wool’s dry, and by then half the fleece will have fallen off,” replied Donald Calum. Duncan Macdonald of Gisla, a man of influence, made the decision: “Let’s press on.” We set off up the track. From the moment we did, the weather improved. We climbed up behind the Gisla pottery, up past lochans and through gates in fences wrapped round the hillside. As we climbed, the view opened up before us to the south, over the bleak, bare moor of the Morsgail Forest. This expanse lies flat and windswept for 20 miles, pitted with burns and lochans like summer tundra. Beyond lie the majestic mountains of Harris, separated by U-shaped valleys. As the weather slowly cleared, I began to pick out individual hills – Clisham, the highest in the Outer Isles with its head in the clouds, and the dark brooding buttress of Strone Ulladale, the largest and most overhanging cliff in Britain, bristling with X-certificate rock climbs.

“But if we don’t go now, we’ll have to wait for a week before the wool’s dry, and by then half the fleece will have fallen off,” replied Donald Calum. Duncan Macdonald of Gisla, a man of influence, made the decision: “Let’s press on.” We set off up the track. From the moment we did, the weather improved. We climbed up behind the Gisla pottery, up past lochans and through gates in fences wrapped round the hillside. As we climbed, the view opened up before us to the south, over the bleak, bare moor of the Morsgail Forest. This expanse lies flat and windswept for 20 miles, pitted with burns and lochans like summer tundra. Beyond lie the majestic mountains of Harris, separated by U-shaped valleys. As the weather slowly cleared, I began to pick out individual hills – Clisham, the highest in the Outer Isles with its head in the clouds, and the dark brooding buttress of Strone Ulladale, the largest and most overhanging cliff in Britain, bristling with X-certificate rock climbs.

We headed for a speck on the hillside – a ruined shieling where Donald Calum searched for a moment before reappearing with a rusted gas stove and some chipped mugs. “I knew they were hidden here somewhere,” he said with a smile. We huddled in what was once a living-room, and boiled water for tea. Soon it was ready, flavoured with milk from a small whisky bottle. The group of us settled down to breakfast alfresco.

The local men hushed for a brief prayer and then relaxed once more. I let the moment wash over me; we sat in isolation and I looked back and forth between the view around me – the horizon to the west, a clear blue line broken only by the Flannan Isles, the only land between us and America – and the group next to me, men laughing and chatting in Gaelic, dressed in Harris tweeds, boiler suits and rolled-down wellington boots.

The sheepdogs interrupted the conviviality as a fight erupted amongst them, a blur of black and white, until peace was restored with a few roars and the odd skelp with a crook, sending them all bouncing off, grinning stupidly at the mayhem they’d caused.

“Here’s where we spread out, David,” said Donald Calum as we packed up to go. “We just walk in line and drive the sheep ahead of us. They’re pretty wild beasts because they don’t see too many people out here, so they’ll just run when you get near them.” Duncan of Gisla, one of our group, added, “Try not to let them break past you. If we miss them today, we won’t get their wool until next year.”

The group split in two – ours went south, the others west, to the sea and back again. This enormous cordon we created – a net stretching from the hills in the north, to the border with Harris in the south – would scoop all the scattered sheep ahead of us and drive them back to the fanks at Gisla to the north-east.

We spread out: Donald Calum went south, to the shores of Loch Resort, the boundary of the Lewisman’s domain. No fence divides Lewis from Harris, but for the sheep, oddly, none is needed. Perhaps the best grazing is in Lewis, but it seems that except for the odd maverick, no sheep heads south, and we picked up no Harris sheep in our sweep. In crofting life, at least, it seems it doesn’t take good fences to make good neighbours!

Half a mile apart, we kept in line, zig-zagging through the heather to drive the Blackfaces east. I began to wish I had a dog to do my sprinting for me, after I’d clambered out from a deeper-than-expected bog.

At midday I spotted Donald Calum taking a seat, a welcome cue for lunch. “What a wilderness,” I said to myself as I sat on a peat-hag, watching a buzzard quartering the ground around me. I knew that between me and Tarbert, 12 miles to the south, there were only a handful of people, including two watchers, men who patrol Loch Resort in the summer in an effort to contain the inevitable poaching from the salmon-rich rivers.

Later, we began to tighten the net on the straggling sheep. The men who had gone west caught us up. They walked high on the hillside, driving the congregating mass of sheep ahead of them, and gradually we tightened the flock, with dogs at the edges and men behind.

We headed for the sheep pens, studying eachother’s herding styles: the dogs, anarchic and keen, bouncing the stragglers back into line; the crofters trying to control the dogs, but resorting to crooks and murderous-sounding Gaelic to intimidate the woolly stragglers; my Uncle Jim finding great success is his gutteral “hut-hut” which he’d apparently learned from a Kashmiri yak-herd in his trekking past; and my own flapping style, lacking in finesse but getting the job done, all moving the sheep towards Gisla.

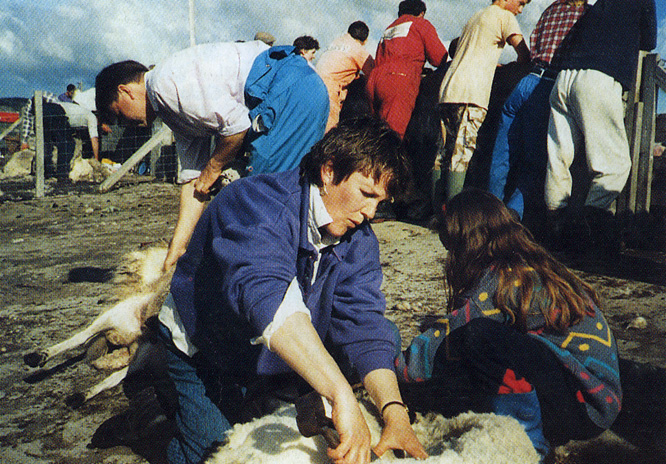

At the fank, the whole community had gathered in anticipation of our arrival, and everyone from grandparents to small children had turned up to help with the shearing. Waiting with the shearers was a crowd of tea-makers, fleece-packers and youngsters keen to learn the ropes.

They had waited for hours. As we came sweeping down the hill, the crowd sparked up. Dogs started to bark, and people swarmed out to help us walk the last half mile. The scene was one of relaxed chaos – sheep, men and dogs wending their way to the fank, stopping all traffic until our convoy of meat and wool reached the shearing pens.

We worked the sheep into the gathering area, the dogs running over the backs of the packed sheep eclear the log-jam. Shearing was ready to begin; but not before the drovers were revived with sandwiches, clootie dumpling and tea made in blackened kettles on the fire nearby.

“Right, Shona, fetch me a sheep,” said Donald Calum. “One of mine, with a blue spot behind the head and a red stripe on the rump.” So the shearing began, with the youngsters wading into the flock like paddlers in the surf, chasing their own marked sheep before frog-marching them to the sheares for a short back and sides, done by hand.Once a sheep was clipped (not an easy job, with damp fleece and unwilling beasts), the fleece was rooled up and packed into a sack. The animal was marked, then returned to the pen for a trip back to the moor. As one shearer tired in the wrists, or the back, another took his place. Women sheared too, fresher than the men, since by custom no woman is allowed to take part in the gathering from the moor. Gradually the queue for clipping dwindled, and the pile of fleeces rose.

“Right, Shona, fetch me a sheep,” said Donald Calum. “One of mine, with a blue spot behind the head and a red stripe on the rump.” So the shearing began, with the youngsters wading into the flock like paddlers in the surf, chasing their own marked sheep before frog-marching them to the sheares for a short back and sides, done by hand.Once a sheep was clipped (not an easy job, with damp fleece and unwilling beasts), the fleece was rooled up and packed into a sack. The animal was marked, then returned to the pen for a trip back to the moor. As one shearer tired in the wrists, or the back, another took his place. Women sheared too, fresher than the men, since by custom no woman is allowed to take part in the gathering from the moor. Gradually the queue for clipping dwindled, and the pile of fleeces rose.

As the crofters finished their work and gathered beside their vans for a whisky and banter, the enormous significance of the sheep drive as a social occasion became apparent. This was one of the most important days in the crofting calendar, when old ties are reinforced and new acquaintances made, stories told and laughter shared. It was good to see the crofting community working together as before, not least because this kind of event is less secure every year.

I would not have been needed on the gather, even a few years ago. “It’s becoming more difficult every year, with fewer young crofters about,” Donald Calum had said. His unspoken worry must have been that, without more young blood, the whole gathering might become impossible in future years.

I would not have been needed on the gather, even a few years ago. “It’s becoming more difficult every year, with fewer young crofters about,” Donald Calum had said. His unspoken worry must have been that, without more young blood, the whole gathering might become impossible in future years.

The community is strong, though, and its essence is the capacity to adapt and find a way, relying on resilience and an ability to cope with what might daunt ordinary suburban folk.

When we finally left the fank and headed again for Valtos, I thought back on the events of the day. There was the gathering of the flock, and the gathering of the crofters – a reaffirmation of the scattered community I was proud to have joined on the day of the sheep.

© David Henderson