Category: Fishing

Morsgail: the History of a Lewis Sporting Estate

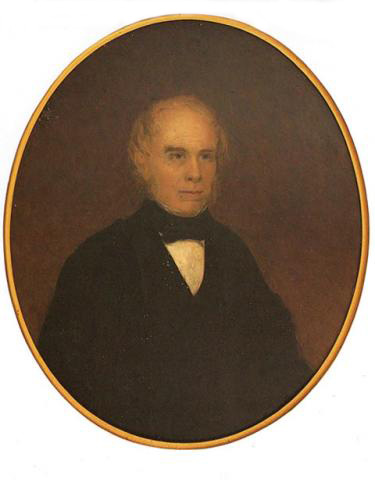

William MacGillivray in Uig

The renowned naturalist William MacGillivray was born in Aberdeen in 1796 and studied and worked most of his life there or in Edinburgh, but he had a Harris connection through his father and spent much of his childhood at Northton in South Harris (where the MacGillivray Centre now bears his name). As a young man, he returned to spend 1817-1818 there, and his diaries of that period have been published as A Hebridean Naturalist’s Journal (Acair 1996). In October of 1817 he and a party of friends and relations made a journey to Uig.

Luachar, Saturday, 18th October.

Let me describe the scenery, shooting grounds, house and its inhabitants. The scenery is generally of the grand order with little or no beauty. We have a long series of lofty mountains, turning into ridges & forming deep glens. These mountains are all rugged & precipitous, they run north-east and south-west. Stretching toward the north from them are low hills and extensive plains several miles in length and toward the south higher hills & vallies. On the declivities and under the rocks are the haunts of the deer, not easily found by a stranger, but well known to the inhabitants. Loch Rezort terminates the ground of sport on the north, the ocean on the west and south, and the Lewes on the east. The whole ground is broken into little eminences & depressions, covered with heath and some other plants – at this season of the year of a yellowish or brown colour, which renders it extremely difficult to see the deer – though the broken nature of the surface facilitates an approach to them when discovered.

The house, our place of rendezvous, is situated at the distance of between one and four miles from the places of resort of the deer, at the head of an arm of the sea which constitutes part of the northern boundary of Harris. It is what in the Hebrides is denominated a black house and what Dr Johnson calls a hut. Its inhabitants are Ewen McDiarmid, a shepherd in the employment of a gentleman of Kintail who has a very extensive tract in Harris under sheep, a tough, unpolished, but honest and civil man advanced in years; his wife Christina McCaskill, daughter of Mr McCaskill schoolmaster of Uig in Lewis, a genteel woman of about thirty; little John their son, a comical cross-grained boy; two female servants, the one a clumsy lump, the other a half-idiot with only one eye.

Luachar, Thursday, 30th October.

On Sunday, the 19th, Ewen and Miss Nelly and I and little John went to Toray, a small farm two miles down Loch Rezort on the Lewis side. One of our incitements to go there was to see two children of Ewen’s who were lodged there. Here we were treated with cream and potatoes. I made a very hearty repast. The vessels which held the cream were only two in number, so the good-man and the good-woman and Ewen were placed about one, while Miss Nelly and I got the other. Had any other arrangement been made, I had been disgusted, and I could not refuse to partake of their fare without being liable to the imputation of pride. We returned in the evening.

Fishing Boats in Uig

On the trail of the Uilleam Dubh

Lighthouse Disaster in the Lews

An enormous shoal of dogs

Provisions for St Kilda, and the Austrian shipwreck

Enterprise of Four Uigeachs

Breanish and Islivig in 1959

Steam Trawling in Loch Roag, 1893

Prosperity and Overcrowding in Uig, 1850s-1890s

Restoring the Rose

no images were found

This article was written by Elly Welch and first appeared in Events. Thanks to Elly for permission to reprint and for the photo of John Macaulay with the Rose. More pictures of the boat (before and during) can be found in the gallery.

Wandering along Valtos harbour a year ago you would hardly have noticed an old relic called Rose. Engulfed in undergrowth, all sun-bleached larch and broken thwarts, she was just another old boat rotting on the shore.

Walk there today and it is a different story. Thanks to Comann Eachdraidh Uig – Uig Historical Society – the pretty ‘double-ender’, one of the few surviving original Western Isles boats, has been restored to something of her former glory. She is unlikely to ply Loch Roag’s tides again but, for now at least, she will be preserved in situ, for posterity.

Rose, a rare example of the dipping lug open-boats once common locally, was built in Uig around ninety years ago. She was gifted to the Comann Eachdraidh last year by Valtos residents who had inherited her, but had no use for her. Previously, she was owned by consortium of local crofters and used for general inshore duties, from shifting sheep to fetching peats and seaweed. Modern boats finally made her redundant around twenty years ago. Since then she has lain where she was last dragged ashore, next to the tumbled walls of an old salthouse and herring store.

By Open Sea from Kinlochresort

An further extract from the unpublished memoirs of Rev Col AJ Mackenzie, born Kinlochresort in 1887. Here he tells of how the family came to be at Kinlochresort, and also how they left it for the gamekeeper’s house at Uig Lodge. His account of the pleasures of Traigh Uig is here.

My father was a gamekeeper who worked on the Gruinard Estate (Wester Ross). It happened he had made the acquaintance of two brothers named Paget who were impressed with his qualities both as a keeper and an all round estate worker. They had taken the fishing and shooting of Barvas, in the Island of Lewis. Dissatisfied with the amount of sport they obtained and knowing that it was capable of much better showing, they asked my father if he would consider coming to Barvas with a view to trying to improve its fishing and shooting. It did not take long to make the necessary arrangements and one day the little family with all their worldy goods and chattels embarked on the good ship Ondine for Stornoway. In due course they found themselves at Barvas and settled in a modest thatched cottage there being no lodge or keeper’s house available. For five years they lived there. It was here the life long friendship began with James Young who leased the bag net fishing rights in several parts of Lewis including Kinresort.

The Pagets ultimately severed their connection with Barvas but the Lewis Estate retained my father’s services and offered him the position of keeper at Kinresort where there was a house that would more adequately meet the needs of the increasing family. The house, unfortunately, would not be available for a year. In the meantime there was the problem of where to live. This was solved by their old friend James Young who offered them accommodation in a house which he owned in Carloway in connection with his salmon fishing. Taking a few necessary pieces of furniture with them and storing the remainder in one of Young’s store house at Barvas, they proceeded to Carloway where they resided a whole year before they finally settled in at Kinresort. It was during this stay at Carloway, that the disastrous fire occurred in the store house at Barvas in which all their furniture was destroyed. The friendship with James Young continued at Kinresort.

The Education Act of 1872 was now in force and large well equipped schools with highly qualified teachers were available in many districts. One of these was in the vicinity of the extensive fishing and shooting of Uig. The head keeper here had no family and when my father suggested to him that they should together approach the Lewis Estate with a view to exchanging spheres, he readily agreed. The proposal was put to the chief authority who was known by the imposing title of the Chamberlain of the Lews.

The Rose

A Herring Girl from Crowlista

no images were found

An account, from the Gaelic, by Christina MacDonald, 25 Crowlista, of her memories of packing the barrels at the herring industry. The picture above is of unidentified Lewis girls at the herring in an unknown port.

See the original Gaelic version here.

When you went to the herring for the first time, you had to be signed on with a curer. The curer would give us one pound to secure our services that was called a pledge. The first place I went was the Island of Baltey in Shetland, across the Balta Sound.

That first year I left Stornoway on the steamship for Lerwick, then a little steamboat from Lerwick to Baltey. We were lying down with seasickness. I would be lying down on the train [?] and on the steamer. Most of the other girls would be sick too – we would recognise the Shiant Isles when we reached them – every girl would then begin to vomit.

They would only give us until the morning after we arrived before they would put us to work – that being if the herring arrived. We would be setting the house in order and the dishes – our trunks would not arrive as fast as we would. We would take with us in the summer, bed clothes, a blanket, and clothes which we would wear. All of our clothes and shoes would have to be in the case. We would take things from the shops in Stornoway that would do us until we returned. It was ourselves that bought the oilskins and the shoes which we had on and leaving our names with them. Even the cloth we would put on our fingers – the strange “yellow calico” – we would bring with us.

We would stay in a wooden shed, which had a small type of stove, that’s all that was there when we arrived until they gave us things, in accordance with what they had. If it was three that was going to be in the room that was all that they would be given – maybe then we would be given a table, but we would sit on our trunks which were kept up by the end of the bed.

There were two beds in the sheds against each other. We would get coal from the master. The girls took turn about washing the dishes and preparing the food. We would buy the dishes, a mirror and a lamp when we would reach over. We would buy everything which the house needed and we’d divide it out amongst ourselves and anything that came was by luck. There was a ballot taken and if you got the dishes you had to do them.

Now, when we began working it was the boys that would take up the herring in the baskets to us and they would put them in a large box. The boys would call it “farlair”. They would fill this box with herring and one of the coopers would put salt into it as they were coming out of the barrels. When we were in England there were a type of basket – they called them swells, they made big barrels for them – they had big wide mouths on them. Two baskets went into each barrel. There was nothing on them to lift them. They went on to the trailer on the horse. There were no cars.

We were not sorting the herring but just as they came out. They were putting salt on them as they came in – no more was put onto them in the box as they took them out one by one. I was not as good at gutting as the rest that was why I became a packer. There were three of us in the crew two gutters and me packing. We would take out the guts and throw them in a box and we would put the herring aside big ones, middlesize ones and small ones- it was in the summer that we would do this. There was a herring brand in the summer the brand was going on them so that the masters would make more money on them, but there was a time of year when there was something on the herring which was making a mess of it unless they took it out. The name was “black bag” – a bulge like the sheep pile.

The Loss of the Margaret

On Saturday, 12 March, 1932, a north westerly gale was blowing and a heavy Atlantic swell was running. When Angus MacKinnon, skipper of the lobster boat, Margaret, saw the inclement weather conditions, he woke his father, Cain, and requested his assistance as an extra hand on the boat. Though retired from fishing, Cain agreed. Angus’s younger brother Calum was also a crew member, but his father decided that he should not accompany them.

At daybreak on that fateful morning, two Brenish boats were launched at Molinish. Strong arms and robust backs were required to haul the boats down the shingle beach and out into the Atlantic swell. With their sails unfurled, one boat headed for the lobster pots they had set opposite Brenish while the Margaret headed in the opposite direction to their pots behind Eilean Mealista.

The Margaret was seen dipping in the heavy swell and about to round Eilean Mealista but was never seen intact again. Paradoxically, the bad weather only lasted for a couple of hours and the rest of the day was calm.